An Ode to the Perfect Food

I have heard that there are places where burritos are not common. I can only imagine those are dark, bleak places full of sadness. Here in south-east Texas at least, burritos are a food group. Actually all of the food groups. Such a delicious orchestration of beans and meat and cheese. Smothered with red sauce? Sure go to town! Green chile sauce? New Mexico says hi! Just more cheese? heh, you do you cowboy! It’s pretty hard to screw up a burrito. I once had one at an Irish restaurant (like I said, Texas). The tortilla was made of potato somehow and it was full of corned beef. But you know what? It was still a delicious burrito!

What does this have to do with PowerShell

I must admit, I kinda want to write a whole article about burritos now. But this is a PowerShell blog so let’s get down to business! This topic was going to be a lightning demo at the 2018 PowerShell and Devops Global Summit, but we had just way too much awesome content. A blog post is probably better anyway, you never want to rush a good burrito story.

Get to the point already!

Ok, ok, here’s the deal. This is a post about using PowerShell to automate the submission of a web form. Specifically the customer survey at www.chipotlefeedback.com. The survey is a multi-page web form with all sorts of unique settings.

We’re going to start with fiddler to figure out what all the traffic is supposed to look like, then move on to PowerShell and play with Invoke-WebRequest to submit the forms and handle the return objects. And finally we’ll look at building our own version of a survey all in PowerShell. So let’s get started! Oh and the finished product is, of course, over on Github

Reconnaissance

The first thing we want to do is figure out what the web traffic looks like behind the scenes when we fill out the survey the normal way. Fiddler is a great tool for just this thing. You start it up, make sure it’s capturing traffic (it usually does this by default), then navigate your website like you normally would in your browser of choice. It will capture all the communication for later review. In our case, we can capture all the back and forth communication for our web survey. After filtering out all the rest of the noise we see something like this:

The layout shows the communication flow on the left side, in chronological order. On the right side, you see the request information on the top, and the response data on the bottom for the selected data. There are several tabs available to show you different parts of the request or response. Since we’re primarily interested in the form submission, the WebForms tab works well on the top half. For the response, I like to use the WebView tab, as that will show me more or less what the response web page looks like. That makes it easy to follow along as you try to correlate between fiddler and your web browser.

So looking at our fiddler trace, it seems relatively straight forward. We appear to be submitting form data to the same URL. We should be able to capture all that data from each request sent, and resubmit them in the same order. Now we just need a nice orderly way to save all that data. Enter everyone’s favorite data structure format, XML! HAHA just kidding, we’re going to use JSON. The below is an abbreviated list of objects, each object being the complete payload for a form submission. So the first object is everything we need to submit the first form, the second for the second, etc.

[

{

"lang" : "en",

"stay_main-pager": "0",

"nodeId": "survey1",

"ballotVer": "2",

"hmac": null,

"is_embedded": "false",

"defPgrAction": "next",

"onf_q_chipotle_survey_invitation_method_alt": "10",

"spl_q_chipotle_receipt_code_txt": null,

"forward_main-pager": "Begin Survey"

},

...

{

"stay_main-pager" : "14",

"nodeId" : "survey1",

"ballotVer" : "10",

"hmac" : "",

"is_embedded" : "false",

"defPgrAction" : "next",

"spl_q_chipotle_customer_first_name_txt" : "Jeremy",

"spl_q_chipotle_customer_last_name_txt" : "Murrah",

"spl_q_chipotle_customer_email_address_txt" : "murrahjm@gmail.com",

"forward_main-pager" : "Finish"

}

]

That’s not too bad, we can just loop through that data and submit each payload in order right? Well almost. We’re making the assumption that all the data we captured is static. We know our survey answers are probably going to be static, but is there other stuff in there that might change? Well to figure that out we’ll just need to do a few more captures. Which means a few more survey submissions, which means a few more receipts. So if you’re following along at home that means eating more burritos in the name of research!

What we find after we are done stuffing our faces with our research is that the nodeId and ballotVer fields seem to change. In fact it looks like nodeID is unique for the whole session and ballotVer changes with each new form request. So that’s something we’ll have to handle as we go along.

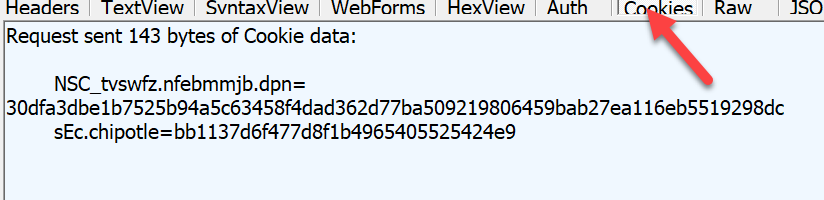

What else do we need? well there’s a cookie in that first packet, so we’ll want to make sure to grab that.

And that should do it! Now let’s write some code!

Invoke-WebRequest

Before we start our little loop of form submissions, we need to make that initial connection. This will give us our session cookies, our session URL, and our initial form page. We’ll start off with the second best cmdlet in PowerShell, Invoke-WebRequest!

$url = 'https://www.chipotlefeedback.com'

#initial connection and retreive first formdata

#also save cookie info in the session variable

$webrequest = invoke-webrequest $url -SessionVariable websession

#form data is here:

$webform = $webrequest.forms[0]

$webform | format-list

Id : surveyform

Method : post

Action : /?feedless-chipotle-rcpt-survey-61c7f7b3df122d691ee3e0ea094ee51d

Fields : {[stay_main-pager, 0], [nodeId, survey5], [ballotVer, 2], [hmac, ]...}

The two things we care about up there are the Action and the Fields. The Action property is what we’ll append to our initial URL to make sure we go to the same form every time. The Fields property is of course our form data, so let’s look at that one.

$webform.fields

Key Value

--- -----

stay_main-pager 0

nodeId survey5

ballotVer 2

hmac

is_embedded false

defPgrAction next

i_onf_q_chipotle_survey_invitation_method_alt_10 10

spl_q_chipotle_receipt_code_txt

i_onf_q_chipotle_survey_invitation_method_alt_20 20

beginButton Begin Survey

Ok that’s a lot of stuff, but what we care about here is the spl_q_chipotle_receipt_code_txt, nodeID and ballotVer. Most of the other stuff we’ll just keep in there. Otherwise it all looks pretty similar to what we saved from our fiddler capture into our JSON file. Oh, so interesting thing with i_onf_q_chipotle_survey_invitation_method_alt_10 and i_onf_q_chipotle_survey_invitation_method_alt_20, those are actually the radio buttons. To select a particular button we just include the root key name (the name above with the _10 or _20 part) and then use the value for the button we want (10 or 20). We’ll see that again in later pages as well. No idea if that’s a common way to do radio buttons, but it’s pretty consistent here. Not a huge complexity, but it helps to eat a few more burritos to have plenty of sample data. Well, help is a strong word but it couldn’t possibly hurt.

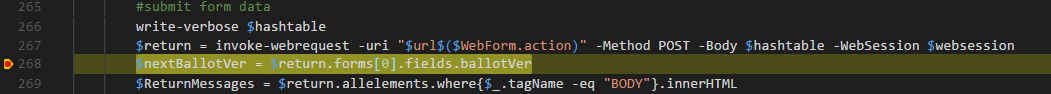

Where was I? Oh right, nodeID and ballotVer. So nodeID appears to be a session-like thing. It sometimes differs between surveys but doesn’t appear to differ between individual form submissions. ballotVer is a little different. At first glance it just looks like a page number or something, incrementing each time. But upon closer inspection it appears to skip a value every now and again. That’s weird, so we’ll just grab it from the return object and apply that value to the next form data.

So armed with all that good info we’re ready to start submitting form data.

#get these initial values

$nodeID = $webform.fields.nodeId

$nextBallotVer = $webform.fields.ballotVer

#$formdata is our imported json data, converted to a PSObject because PowerShell is like that

foreach ($item in $formdata){

#update nodeID field

$item.nodeId = $nodeID

#set current ballotVer to the value specified by the previous return

$item.ballotVer = $nextBallotVer

#PSObjects are cool but we need a hash table for Invoke-WebRequest

#so we use some function I found on the web, IDK

$hashtable = $item | ConvertPSObjectToHashtable

#submit form data

$return = invoke-webrequest -uri "$url$($WebForm.action)" -Method POST -Body $hashtable -WebSession $websession

#write the returned ballotVer value to retrieve the next time around

$nextBallotVer = $return.forms[0].fields.ballotVer

}

Did that work? We didn’t get any errors, so… yes? Maybe? Well follow along dear reader, and let’s take a journey through our data to answer that question with a little more certainty!

Finding Errors and Debugging

The funny thing about computers is that they tend to answer the questions that we ask, not necessarily what we meant to ask. For instance, if you submit form data with Invoke-WebRequest, and look for a return code, what you are actually asking is “did the POST operation succeed?” to which the web server will likely return “yes, return code 200 = success”. However, what we might have really wanted to know was something like “was my data correct and accepted by the form submission process?” That’s something a little different. The answer is in there, but in our test case it’s buried a little deeper than a return code. But first let’s think about things that could go wrong with our data submission.

- The receipt code is invalid

- The receipt code has already been used

- The form data was not expected or sent out of order

The question then is, what does the data look like for each of these errors? Well the best way to find that out is to do it! Submit a bogus receipt code, submit a good receipt code twice, munge up your json doc and send that. The error text will be somewhere in the return data from the Invoke-WebRequest call. The tricky part will be finding it, but one thing at a time.

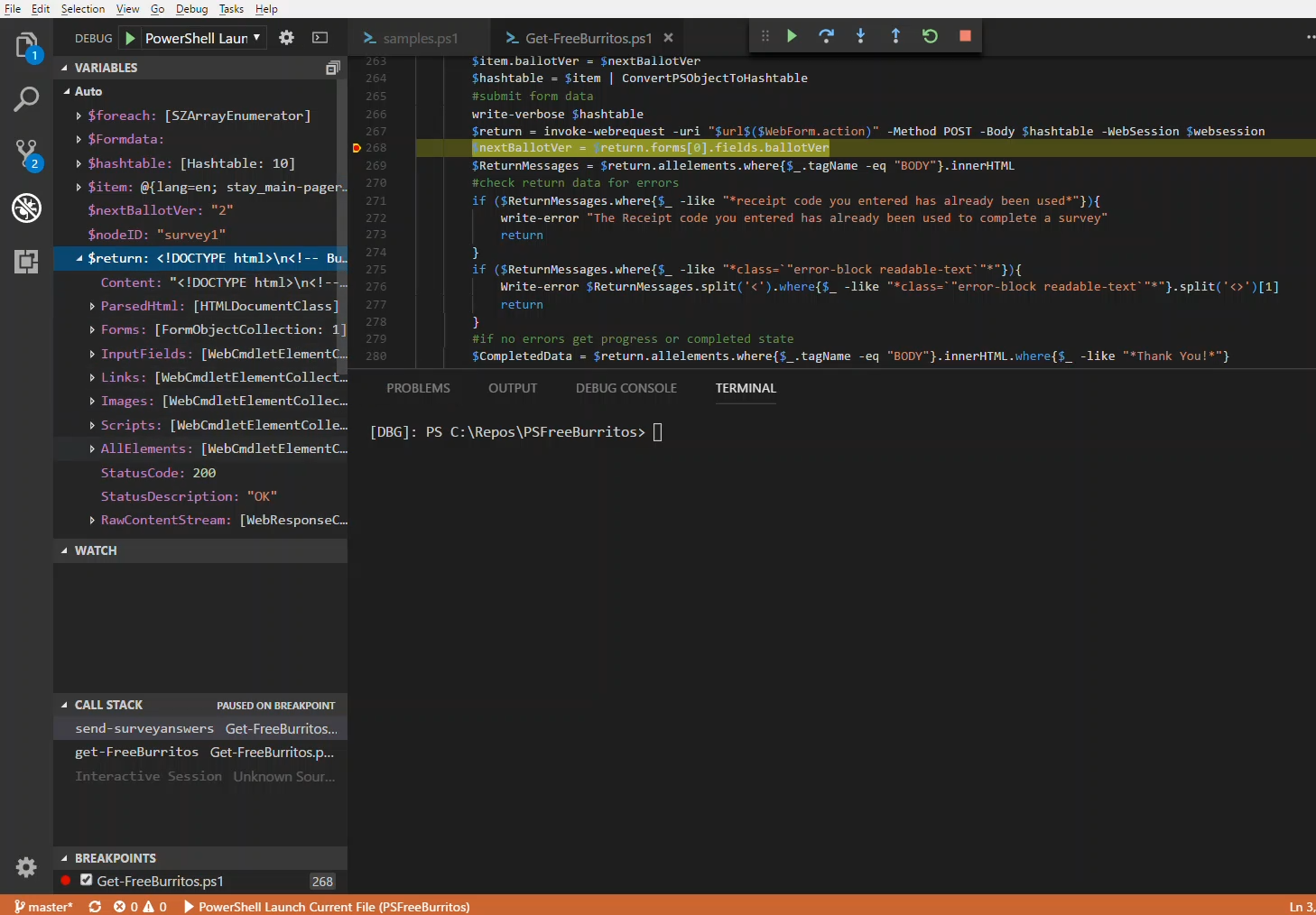

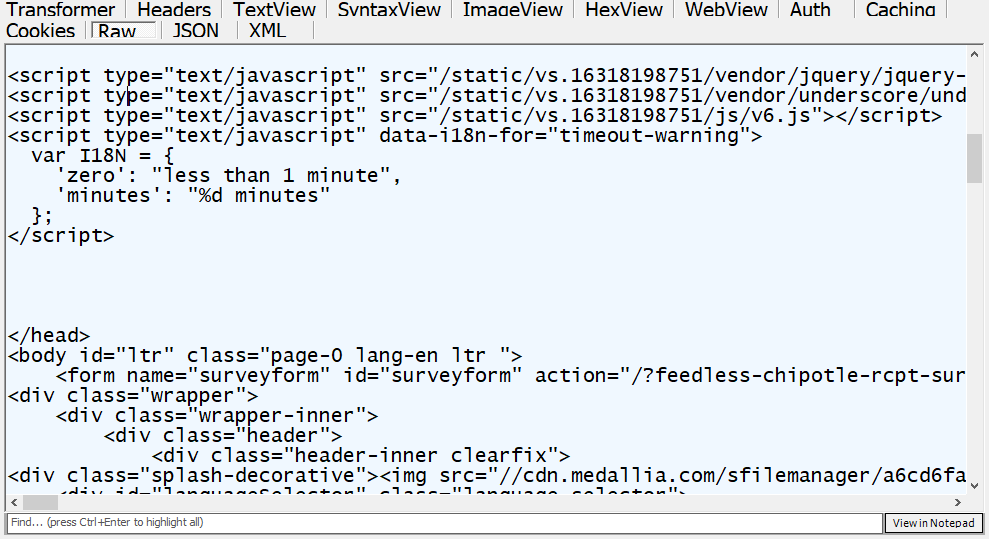

A really great way to look at something like this while our script is running is with a debugger. We can have it pause right when we get our return payload and browse around our data while it’s still in memory. So let’s do that! This article on debugging is a great primer to get started. Also this Pluralsight course is pretty great also. So go check those out if you’re not entirely familiar with the VSCode debugger and come on back. (Hint: that article takes about 1 burrito worth of time to read, so, you know. Research.)

Ok, so now that you know kung fu debugging, let’s get to it!

We’ll test our invalid receipt code scenario first. Let’s do three things to set up our environment before hitting the big red button:

- Set a break point right below this line in our main function:

$return = invoke-webrequest -uri "$url$($WebForm.action)" -Method POST -Body $hashtable -WebSession $websession

- open up a new PowerShell script file to help launch our debugger:

. .\get-freeburritos.ps1

get-FreeBurritos -ReceiptCode 00000000000000000000 -answerfile .\sampleformdata.json

- Open fiddler and set it to start capturing so we can gather the web data as we hit our break point

Now that we’re all set hit F5 to start up your script.

Once we hit our break point, we should have one captured packet in fiddler. Let’s grab the raw output of the return packet and copy/paste it over to notepad to do a quick search.

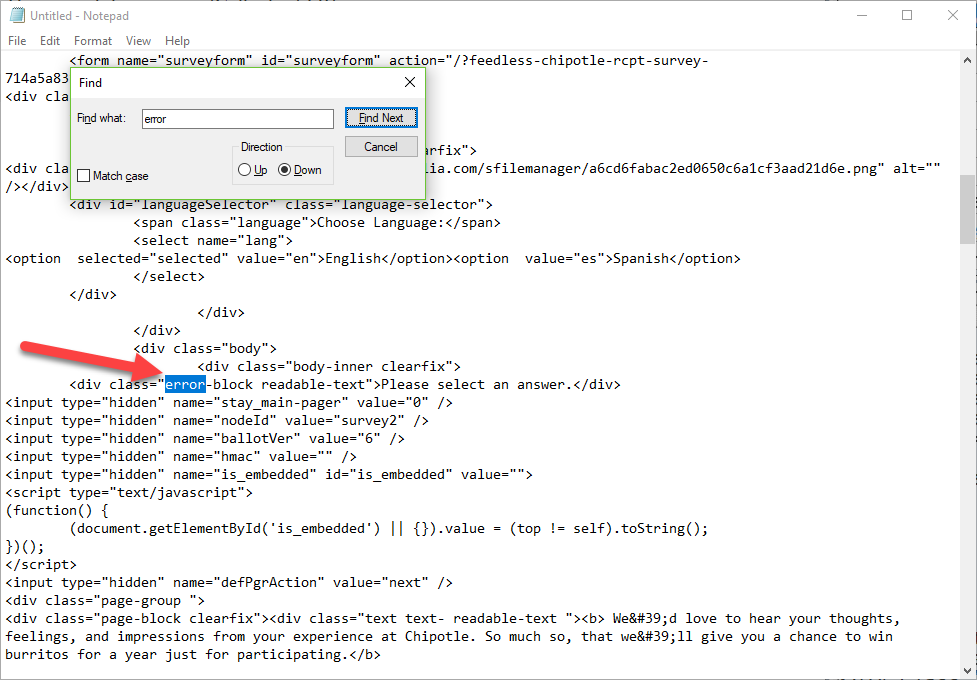

There’s a ton of data there but let’s see if we can get lucky. Let’s search for the word “error” and see what we find.

Wow we found something! error-block readable-text that sounds like an error message. Ok now that we have that element, let’s go over to our debugger and see if we can find that section. We have the $return variable that should be populated with all this data, so we can just browse that like so (click for GIF-y goodness):

Look at all that data! That message is really buried under there. But that’s ok, we’ve found it so we know what to look for now. Cleaning up our request we can do something like this now in our script:

$ReturnMessages = $return.allelements.where{$_.tagName -eq "BODY"}.innerHTML

if ($ReturnMessages.where{$_ -like "*class=`"error-block readable-text`"*"}){

Write-error $ReturnMessages.split('<').where{$_ -like "*class=`"error-block readable-text`"*"}.split('<>')[1]

return

We’re making the assumption here that the generic-sounding error-block readable-text class is in fact a generic error message. Based on that assumption we’ll just output the error message as a PowerShell error object, then bail out of our script. (It turns out this covers scenario 3 as well, so that’s cool)

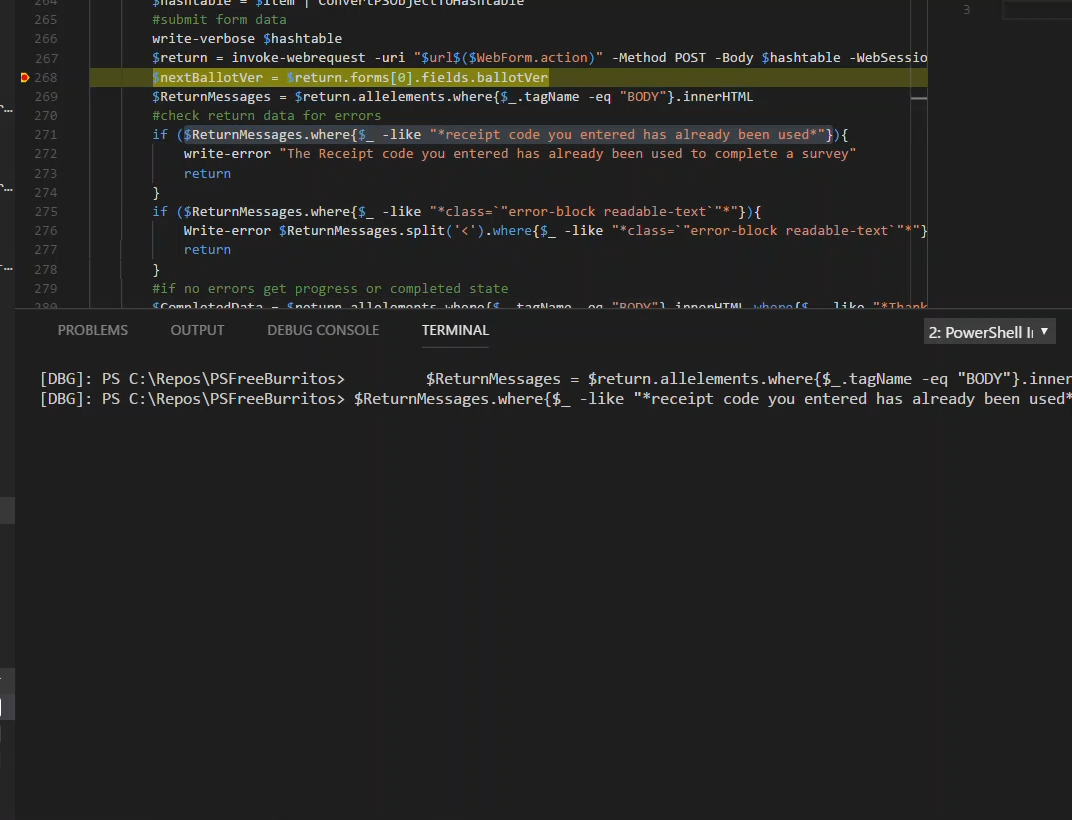

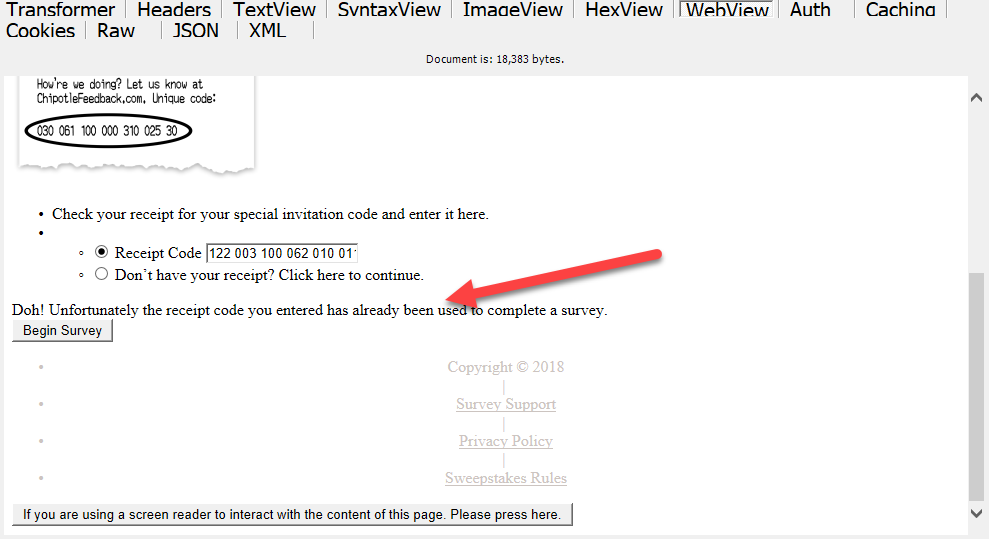

What’s next? Ah, what about a re-used receipt code? Well the same process applies more or less. We’ll do our debugger and our fiddler trace, then look at our return packet. This time let’s look at the web view.

That looks like some error text to me. I’d bet that’s probably in the same place as the other message, so let’s go straight to our debugger and query that $returnmessages variable.

$ReturnMessages = $return.allelements.where{$_.tagName -eq "BODY"}.innerHTML

$ReturnMessages.where{$_ -like "*receipt code you entered has already been used*"}

Wow that’s a lot of output. That would take some work to filter down to just that message, but fortunately we don’t have to do that. Just the existence of that text is enough to tell us that we had an error, so we can just craft our own error message and call it a day.

write-error "The Receipt code you entered has already been used to complete a survey"

return

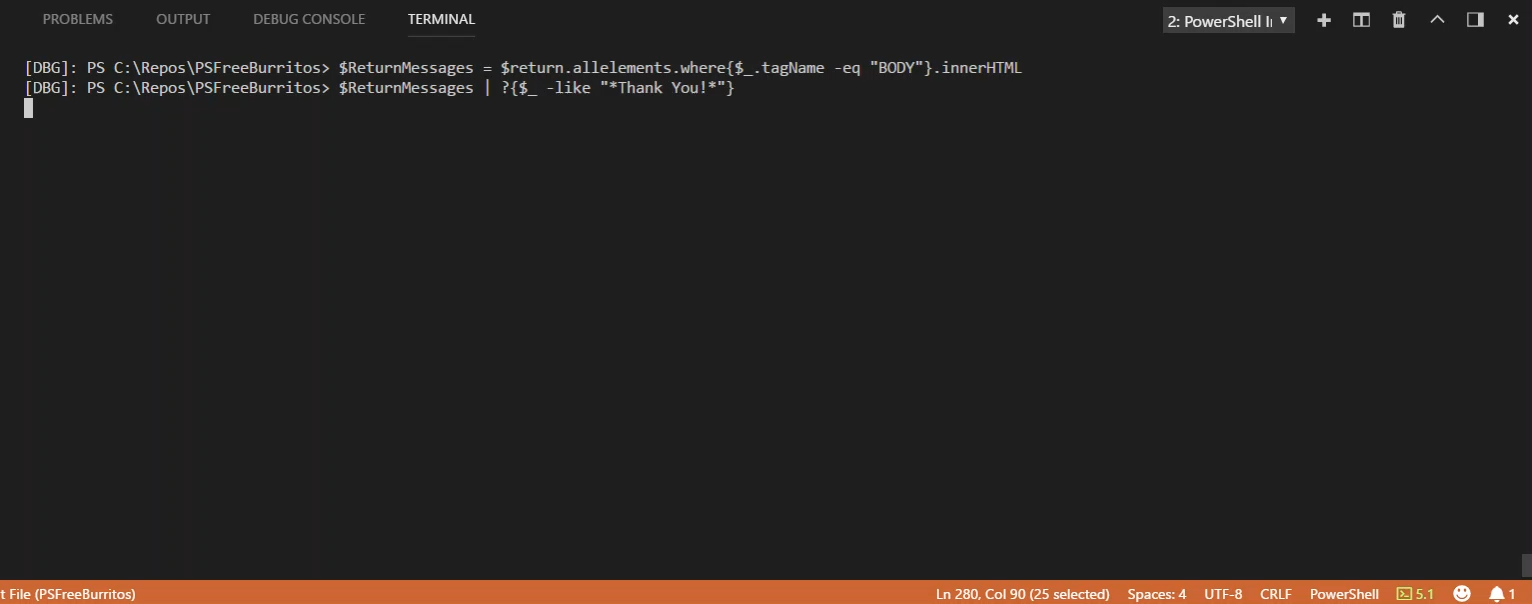

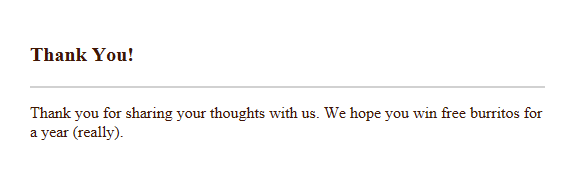

Enough errors, what about success?

Debugging is like, such a drag man, so much negative thinking with, like, the errors and stuff. Got to think positive man, good vibes and such.

Knowing when we hit an error is great, but we probably want to know when we succeed too. In theory if we don’t get an error we are probably completing the form successfully, but it never hurts to double check. If we do another fiddler trace of a successful submission with our debugger on, we see this at the end.

That sounds definitively successful to me, so let’s see if we can find that in the debugger output

$ReturnMessages = $return.allelements.where{$_.tagName -eq "BODY"}.innerHTML

$ReturnMessages | where-object{$_ -like "*Thank You*"}

Bingo, there’s our success message. If you were following along at home, as you were stepping through the debugger you might have noticed another piece of data that blinked by. Let’s look again:

Did you catch that surveyprogress value? That looks like an incrementing value between 0 and 100. What could we do with that? ooh how about a progress bar!

Muahahahahahaa!! Gimme those free burritos baby! Packaged all up now we’ve got ourselves a script! Well, I’ve got a script. But I want everyone to have free burritos. Like a burrito fairy or something. Up to this point we’ve been interacting with our saved JSON file. It works, but it’s not the most user friendly thing in the world. Ideally we’d anyone using this tool would be able to craft their own JSON file by answering survey questions, without the need for a fiddler trace and all that. The next section will focus on all that. But in the meantime all that debugging left me famished. Time for a burrito snack!

The Survey

Whew! That was a lot to unpack up there. Almost like a… no, scratch that. I think I’ve reached my quota of bad burrito puns at this point. So let’s just proceed with the PowerShell. In this section we want to take what we’ve built above and wrap up all that goodness in a convenient package. Something you could hold in two hands perhaps? NO! We’re done with the puns! Ok where was I? Oh right, we want to build something a little more user friendly than editing a JSON file. The web form that we started this whole thing with is more or less what we want, but we should PowerShell it because why not?

Our survey form should do three things:

- Gather all the survey answers and validate the values

- Convert the answers to the format expected by the server

package the answers into the form data array of JSON objects and pass them to the submission function

- oh and optionally export the packaged data out to a file

That doesn’t sound to bad. Let’s tackle those one bite at a time. (dammit!)

Gathering Inputs

Ok for the survey there are a few ways we could go about getting that data. The first thing that comes to mind would be our old friend Read-Host.

PS P:\> $tasteoffood = read-host -Prompt "On a scale of 1 to 5, how would you rate the taste of your food"

On a scale of 1 to 5, how would you rate the taste of your food: 5

PS P:\> $tasteoffood

5

That’s not bad, it certainly looks like a survey. But, there’s nothing stopping anyone from entering anything in response. We’d have to add some code to verify that input, maybe throw an error if it’s invalid, or try again or something. We have a lot of questions to go through so that could get tedious quick.

Another way to handle it would be to define all the inputs and validations in the param block. That’s a little cleaner than coding all the validation ourselves.

[Parameter(Mandatory=$True,

HelpMessage='On a scale of 1 to 5 how would you rate the taste of your food'

)]

[ValidateSet('1','2','3','4','5')]

[String]$TasteofFood,

That’s pretty clean, but it’s not the best looking interface. Here’s what we get if we run that:

Get-FreeBurritos

cmdlet Get-FreeBurritos at command pipeline position 1

Supply values for the following parameters:

(Type !? for Help.)

TasteofFood: !?

On a scale of 1 to 5 how would you rate the taste of your food

TasteofFood: 5

PowerShell doing it’s thing there, so it’s just going to prompt us for a parameter name, rather than the nice pretty survey question we had in mind. Of course we can always hit !? to get the full question, but honestly, have you ever actually used that feature? I mean it’s there, so it’s not terrible, but not perfect.

In thinking about this problem I did stumble across a third way. A dark, stormy way that is most certainly a bad idea. An unholy combination of the above two methods that oddly enough seems to actually work.

param(

[Parameter(Mandatory=$True)]

[ValidateSet('1','2','3','4','5')]

${On a scale of 1 to 5 how would you rate the taste of your food}

)

You would be right if your first reaction was WTF is that?!? You would also be right if your next thought was Does that nonsense actually work? It does actually, well sort of. Let’s look at our output:

Get-FreeBurritos

cmdlet Get-FreeBurritos at command pipeline position 1

Supply values for the following parameters:

On a scale of 1 to 5 how would you rate the taste of your food: 1

Now that looks like the kind of survey question we want to actually ask! And because it’s in the param block we still have our parameter validation and all that. The downside is that our variable name is rather unwieldy, and in fact in our function any time we want to use that variable we have to reference the whole thing like this:

write-output ${On a scale of 1 to 5 how would you rate the taste of your food}

Also tab completion on the command line gets totally confused and you can’t really type it all out on the command line at all.

You could add an alias value to it and specify that on the command line, but our tab completion won’t pick that up. So not a perfect solution either. And to be honest there are probably other reasons why it’s bad, but it was pretty interesting that it worked, so something to consider for your next survey-related endeavor.

Formatting Data

At this point we’ve chosen one of the above methods (I won’t judge!) and proceeded to create a very large host of inputs. Now that we have all this data what do we do with it? Well remember the JSON file from earlier?

[

{

"lang" : "en",

"stay_main-pager": "0",

"nodeId": "survey1",

"ballotVer": "2",

"hmac": null,

"is_embedded": "false",

"defPgrAction": "next",

"onf_q_chipotle_survey_invitation_method_alt": "10",

"spl_q_chipotle_receipt_code_txt": null,

"forward_main-pager": "Begin Survey"

},

...

{

"stay_main-pager" : "14",

"nodeId" : "survey1",

"ballotVer" : "10",

"hmac" : "",

"is_embedded" : "false",

"defPgrAction" : "next",

"spl_q_chipotle_customer_first_name_txt" : "Jeremy",

"spl_q_chipotle_customer_last_name_txt" : "Murrah",

"spl_q_chipotle_customer_email_address_txt" : "murrahjm@gmail.com",

"forward_main-pager" : "Finish"

}

]

Yeah that’s the one! Well all we have to do is recreate that! Simple right? Well I had a friend that used to tell me “If you’re not cheating you’re not trying” so let’s cheat a little! We’re going to include a sample json file with our module and just import the contents on the sly. So now we have an array of objects already in the format and order that we want it in.

$formdata = get-content "$PSScriptRoot\sampleformdata.json" | convertfrom-json

Now we just have to replace the form values with our survey answers! That gets a little tedious but not super complicated. We end up with two methods for doing that. For some of our answers it’s as straight forward as setting the value:

$formdata[0].spl_q_chipotle_receipt_code_txt = $formattedReceiptCode

$formdata[1].onf_q_chipotle_overall_experience_5ptscale = $OverallExperience

$formdata[1].spl_q_chipotle_reason_for_score_cmt = $ReasonForScore

For our radio buttons we have to do a little more work. Remember above when I mentioned that they have a somewhat cryptic method of storing the radio button selection? They use a value of 10 or 20 or 30 or some increment like that to specify which button is selected. Well we definitely don’t want our survey question to ask for an answer of 10 or 20, we want human words like ‘Dine-In’ or ‘Carry-Out’, etc. So let’s use the good ol’ switch construct.

Switch ($ExperienceType){

'Dine-In' {$formdata[2].onf_q_chipotle_experience_type_alt = '10'}

'Carry-Out' {$formdata[2].onf_q_chipotle_experience_type_alt = '20'}

'Catering' {$formdata[2].onf_q_chipotle_experience_type_alt = '30'}

'Delivery' {$formdata[2].onf_q_chipotle_experience_type_alt = '40'}

}

That’s not too bad actually. Relatively straightforward transformation from our survey answer to our submission code. We’ll do a little rinse and repeat on that and eventually end up with all our answers in the right format. Great! Now we’ve updated our $formdata variable with all of our data and we can simply send that over to our submission function and boom we’re all set!

But wait there’s more! Order now and receive two for half the price! Ok not really that much more but since we are probably going to submit this form data more than once (I mean you either love burritos or you don’t right?) we might as well save ourselves from having to answer the questions every day. So let’s say we make a switch parameter called $ExportAnswerFile. And we’ll then dump our $formdata out to a JSON file if that is selected. Then tomorrow (or later today, again no judgement here) we can pass in that JSON file instead of answering the questions again.

If ($ExportAnswerFile){

$formdata | ConvertTo-Json | set-content -Path "$PSScriptRoot\SurveyAnswers.json"

}

Profit!

I’m not sure how I thought I’d squeeze this into a 10 minute demo, but I’m glad I decided to write it down. Burrito-specific context aside, I hope this has been a helpful dive into how you can interact with form data through PowerShell, and also how the debugger can really help explore these web request data structures. Also the survey stuff, while not as ‘exciting’ or ‘complex’ as the first section is an interesting take on some of the different ways to gather data from inputs and provide the interface that squishy human-types seem to like. That variable-encapsulating-a-sentence thing is weird and gave me a chuckle when I saw that it kinda worked. PowerShell never seems to run out of little secret gems like that.

Anyway, I hope you got something out of this post. The complete code for this project is on my PSFreeBurritos repo on github. If you have any questions about it or see something that is totally wrong or just plain dumb, hit me up on the Twitters or use that comment form below (I think it works now). And until then, may you live a life like a burrito, full of joy and smothered in cheese.